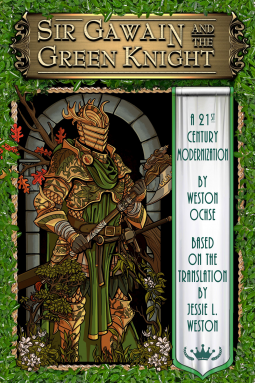

Review: 'Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: A 21st Century Modernization' by Weston Ochse, with Jessie L. Weston

Pub. Date: 07/30/2021

Publisher: Dark Moon Books

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight stands as one of the earliest literary memories of Medieval England, King Arthur and his Round Table, the mythical Camelot, and those knights who called it home.

In this classic tale of chivalry and adventure, a mysterious figure interrupts a New Year’s Eve celebration. Dressed all in green, he challenges King Arthur to a dangerous duel, but it is Gawain, the least of them, who is brave enough to accept the challenge on Arthur’s behalf. What follows is the young knight’s journey into the heart of darkness as he tries to survive the impossible.

Intended for students, academics, and fans of the Knights of the Round Table mythos, no treatment or contemporary retelling of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is as complete and thrilling as this Dark Moon Books edition by USA Today bestselling-author Weston Ochse!

Included in this comprehensive edition are:

• The original 1348 tale of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight in Middle English verse

• Jessie L. Weston’s 1898 poetic translation of the original Middle English version

• Acclaimed author Weston Ochse’s 2021 modernized narrative of the story

• Supporting preface by the author

• Afterword by Unconventional Warfare Scholar, Jason S. Ridler, PhD

• Interior Illustrations by Yvonne Navarro

• … and more!

First, some background! Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is a poem written in the late 14th-century. It falls within the chivalric romance genre and is written in a North West Midlands dialect of Middle English. It only survives in a single manuscript and is written in an alliterative form which follows a "bob and wheel" rhyming scheme which gives the poem a great sound when read aloud. The poem tells the tale of young Gawain, a young man at Arthur's court, who takes up the challenge of a Green Knight who appears in Camelot on New Year's Eve. The challenge? Gawain may strike the Green Knight with the latter's axe now, but must accept a similar blow in a year and a day's time. Gawain cuts off his head, but the Green Knight picks up his head, repeats the appointment for in a year's time, and departs. The rest of the poem follows Gawain as he gets ready to meet this appointment and the challenges to his sense of honour, loyalty, and virtue he faces along the way. It is a stunning poem and probably my favourite piece of Arthuriana. I'm a literary Medievalist by trade, but as I focus mostly on literature in Old English and Old Norse, my Middle English is actually pretty atrocious. (It's the French influence, it just shuts my Germanic brain down... #excuse). As such, I have often used translations to get a grip on the original text, and I always enjoy discovering new ones. My favourite translation so far is Simon Armitage's, as he brings a flavour to the poem which matches its original dialect. The issue with translations, of course, is that it is never the original and something is always lost (but hopefully also gained) in the process of translation. As such, I was very intrigued by what Weston Ochse would do with this "modernization".

There are a lot of aspects, or layers, to Oche's Gawain, as the blurb suggests. This book is an attempt at a comprehensive edition, one which shows various layers and versions of the poem to a non-academic audience. Ochse's Preface makes this non-academic focus very clear and I did run into some issues there. Full disclosure: I am but a junior academic, not even halfway through a PhD, but technically I am part of what one might consider the "academic establishment". It is not at all my desire to gatekeep poems like this, I fully support accessible, popular, and non-technical editions that everyone can enjoy. Ochse is completely correct in hoping that everyone can add something to our understanding of poems like these, not just dusty academics like I one day hope to be. So, on the one hand, it is on me that I had some issues with the Preface, as I'm not the target audience for this edition and knew that going in. But on the other hand, I don't think it is entirely correct to state that 14th-century England was interested in turning people into 'a zombie horde of virtue-signaling Gawains' (5%). For a poem that actually rather deftly interrogates ideas of virtue, facades, morality, and integrity, that rings false to me. I didn't entirely enjoy the way the Preface stated some things, which means I wouldn't, for example, be able to use it in the classroom. Ochse's translation, however, absolutely did the trick for me. I enjoyed how well it flowed, how modern it felt and yet how recognisably like the Middle English poem. His word choices worked for me, as did the translation into prose rather than poetry.

What really makes Ochse's Gawain stand out from other translations/editions, even ones I love like Armitage's or Tolkien's, is that it layers multiple versions of the poem atop each other. We start with Ochse's modern prose translation, which makes the poem immediately accessible to a 21st-century audience. As Ochse himself was strongly influenced by Jessie L. Weston's 1898 translation (more so, perhaps, than by the Middle English version) her translation follows second, giving us a glimpse at how a Victorian audience received this poem, which elements she highlighted and which she removed. Her two Prefaces are also very interesting and I'm glad they too were included. Third comes the Middle English poem. I'm not entirely sure where the 1348 date comes from, as the last time I read up on the poem it was more commonly dated to the last quarter of the 14th-century, or even early 15th-century. I also don't know which edition they're using, i.e. whether Ochse edited the poem himself from the manuscript or whether it is Tolkien and E.V. Gordon's definitive edition, which we still use in university courses. Whatever it is, I think it should be noted, either to properly reflect Oche's work or to credit the original editor. I did enjoy how it highlighted the bob and wheel rhythm of the poem, which I think is another step towards making it a little more accessible. The book ends on an Afterword by Jason S. Ridler who advocates for allowing stories to change, modernise, and adapt throughout the years. I am fully behind this, as my love for Maria Dahvana Headley's irreverent yet stunning translation of the Old English Beowulf should show.

I overall very much like the approach and aim behind Ochse's Gawain. I think it is great to bring a medieval text into the modern world so extensively by including both translations and the medieval text. That way, when people have familiarized themselves with the translations, they can have some fun playing around with the medieval language. That's how I got into Old English as a 17-year old! It is also good to have the Middle English alongside other version because medieval literature itself was not as obsessed with the "original" or "true" version of a story as we are now. Stories existed in various versions, each adding their own elements, removing others, and creating new layers of interpretation. (We medievalists call this variance.) With some poems, like Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, we only have the one manuscript (known as a "manuscript witness"), whereas for other stories there are many more. (For example, of the Middle High German Das Nibelungenlied, from around 1200 CE, we have over 30 manuscript witnesses!) As such, with medieval literature the written manuscript version we have now is not necessarily the capital-O Original. The story may have existed in other manuscripts now lost, it may have been an oral poem beforehand, or perhaps it was indeed a composition by the person known as the Gawain-poet who was inspired by other Arthurian tales. Just because this manuscript version is the only one we have does not mean we should consider it the only "true" version. Each edition, translation, and adaptation, whether academic, like Tolkien and Gordon's 1925 edition, or popular, like Ochse's translation or the A24 film adaptation, are valuable in and of themselves. This doesn't mean I don't still have issues with some of the comments in Ochse's Preface or the lack of information on where the Middle English text comes from, but they are my only real gripe with this Gawain modernisation. They are also not gripes with the book or its aim, but rather with my desire for the historical context to be correct and objective, if you choose to bring it in at all. The beauty of literature is that there is space for a lot of divergent opinions and interpretations and I have no quibble with anyone who interprets a text differently than me. But we can't really disagree on the history around the text, I think. So while I don't think I could use this book as a primary source in one of my university courses, I absolutely would recommend it to those interested in engaging with the Gawain poem in its different iterations.

I give this book...

3 Universes!

This Modernization of the Gawain poem offers a lot of different insights into the Middle English poem and its long afterlife. The fact that a poem from the 14th-century can continue to inspire centuries later is in and of itself amazing, and getting to see these different takes on the poem layered on top of each other provides a really interesting reading experience. For those interested in learning more of the poem's background and themes, I would recommend digging into the academic literature around it, however, much of which is also accessible online.

Also, go have a look at the manuscript, which can be found fully digitised on the University of Calgary website.

I had a picture book of Gawain and the Green Knight as a child when I was barely able to read. I remember looking at it over and over again. It was one of the few books we had in our bookcase.

ReplyDeletehttps://bookdilettante.blogspot.com/2023/04/i-cant-save-you-memoir-by-anthony-chin.html

A picturebook of Gawain and the Green Knight was one of the few books in our bookshelves in the countryside where we grew up. I landed up rereading it many times, for the story and the illustrations.

ReplyDelete